Australia’s Social Media Ban Is Unlikely To Help Young People

Australia's social media ban is confusing and fails to help young people.

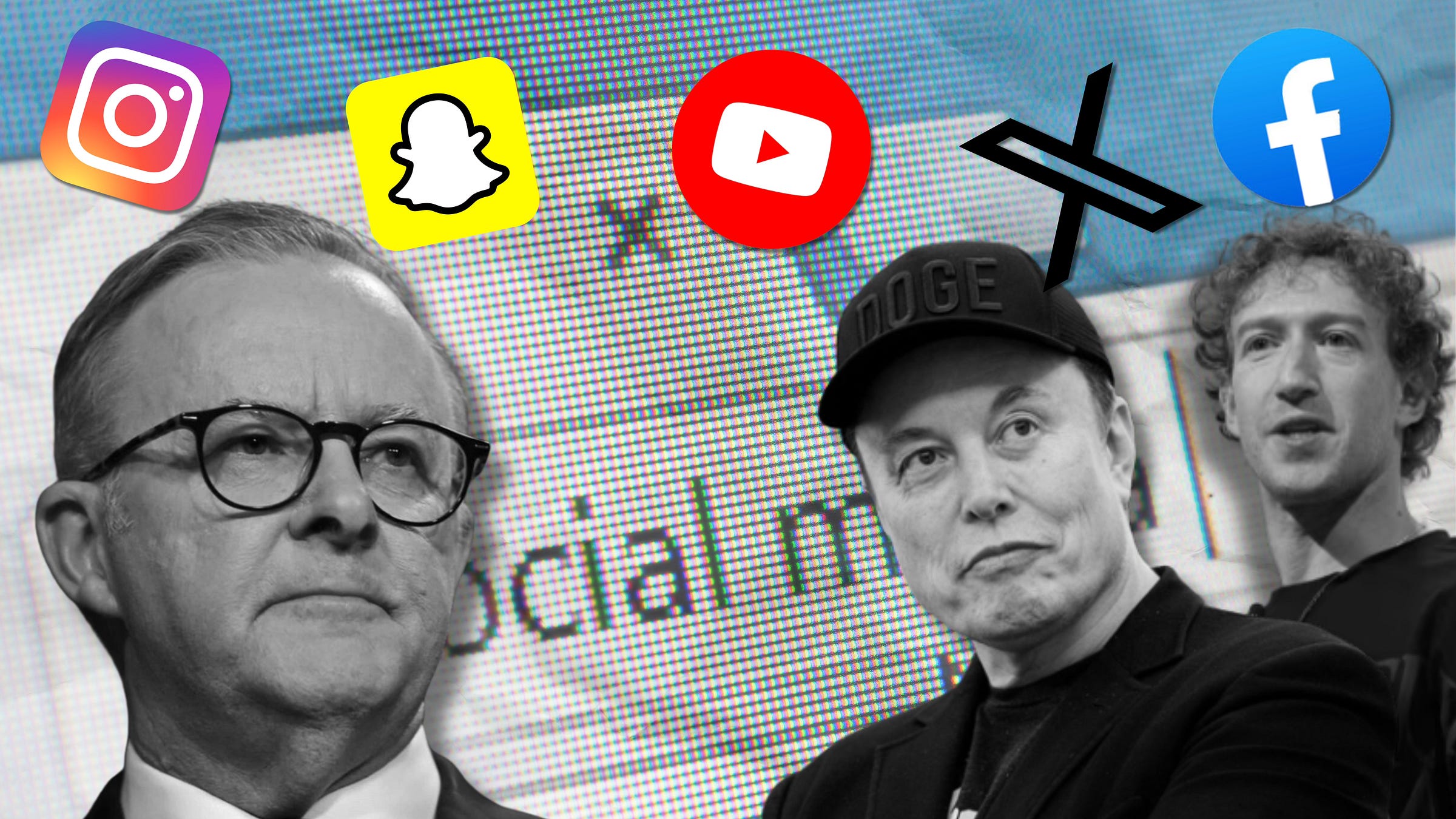

AUSTRALIA—Months prior to Australia’s May 2025 Federal election, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese confidently stood up before the Canberra press gallery declaring “social media is doing social harm to our young Australians and I am calling time on it”. In his speech, Mr Albanese vowed to introduce world-leading legislation, which increases the legal minimum age for accessing social media platforms from 13 to 16 years of age.1 This legislation also requires tech companies take ‘reasonable steps’ to enforce this ban, with the ban taking effect in December 2025. This announcement, influenced by South Australian Premier Peter Malinauskas’s own proposal and Newscorp’s ‘Let Them Be Kids’ pressure campaign, aims to address raising social media addictions amongst generation Z, although despite the ban’s novelty, it is difficult said than done.

Under the Act, social media platforms, such as Meta’s Facebook & Instagram, Elon Musk’s X and Gen Z’s favourite TikTok, are defined as ‘age-restricted social media platforms’, however video streaming platform YouTube, will be exempted. To actually enforce this social media ban, the Albanese government in conjunction with the eSafety Commissioner, hosted the Age Assurance Technology Trial (‘AATT’), to recommend possible age verification systems to be adopted by tech companies. The AATT will likely recommend people supply personal information to verified third party platforms for age certification, or more controversially, users submit pictures of their faces for A.I. verification. Face verification, despite its efficiency has its flaws, it currently holds a maximum success rate of 85% amongst people under 18, with people as old as 37 being misidentified (although these margins of errors have narrowed in recent years). Social media platforms who fail to comply with the Act are liable to fines up to $50mil, amongst other costs arising from legal challenges.

Gen Z, the target of the proposed law, is the first generation to grow up alongside the advent of social media, either those posting in the primitive days of Myspace, to the 60% who scroll TikTok religiously. These perceptions, including that the stereotype that Gen Z is “dopamine pilled”, hold factual truth, According to the Menzies Research Centre social media usage peaks at 17 years of age with users averaging 5.8 hours per day, or 62% spending 4+ hours on social media daily - approximately 28 hours per week.

However, despite the novelty of Australia’s social media ban, which has been imitated from entrenched bureaucracies in Brussels, to deep-red Florida in the United States, it’s actual benefits to young people remain unclear.

First, the proposed law with its lofty ambitions, will be difficult to enforce and administer and perhaps most importantly, it is fraught with lawsuits from overzealous lawyers from mighty tech giants interested in retaining their authority over their platforms against any government oversight - justified or unjustified. Age verification systems for users in Australia already exist following amendments to the Online Safety Act 2021 (Cth) which required platforms such as Google, to require users provide government identification to access 18+ content online. This included either providing some form of government identification or credit card information to Google. Most young people lack proper identification, and understandably, given Google’s recent June 2025 data leak, may not be comfortable sharing their credit card information - instead they could opt for A.I. facial recognition. Most facial recognition models according to the AATT can guess a user’s age within a year, however as this is not always accurate, with some studies suggesting people with darker skin (who are underrepresented in training data) experience larger age gaps. Either way, both options will be unpopular with people, especially if extended to people over 18, who may not be comfortable sharing more personal information with Mr Musk or Mark Zuckerberg.

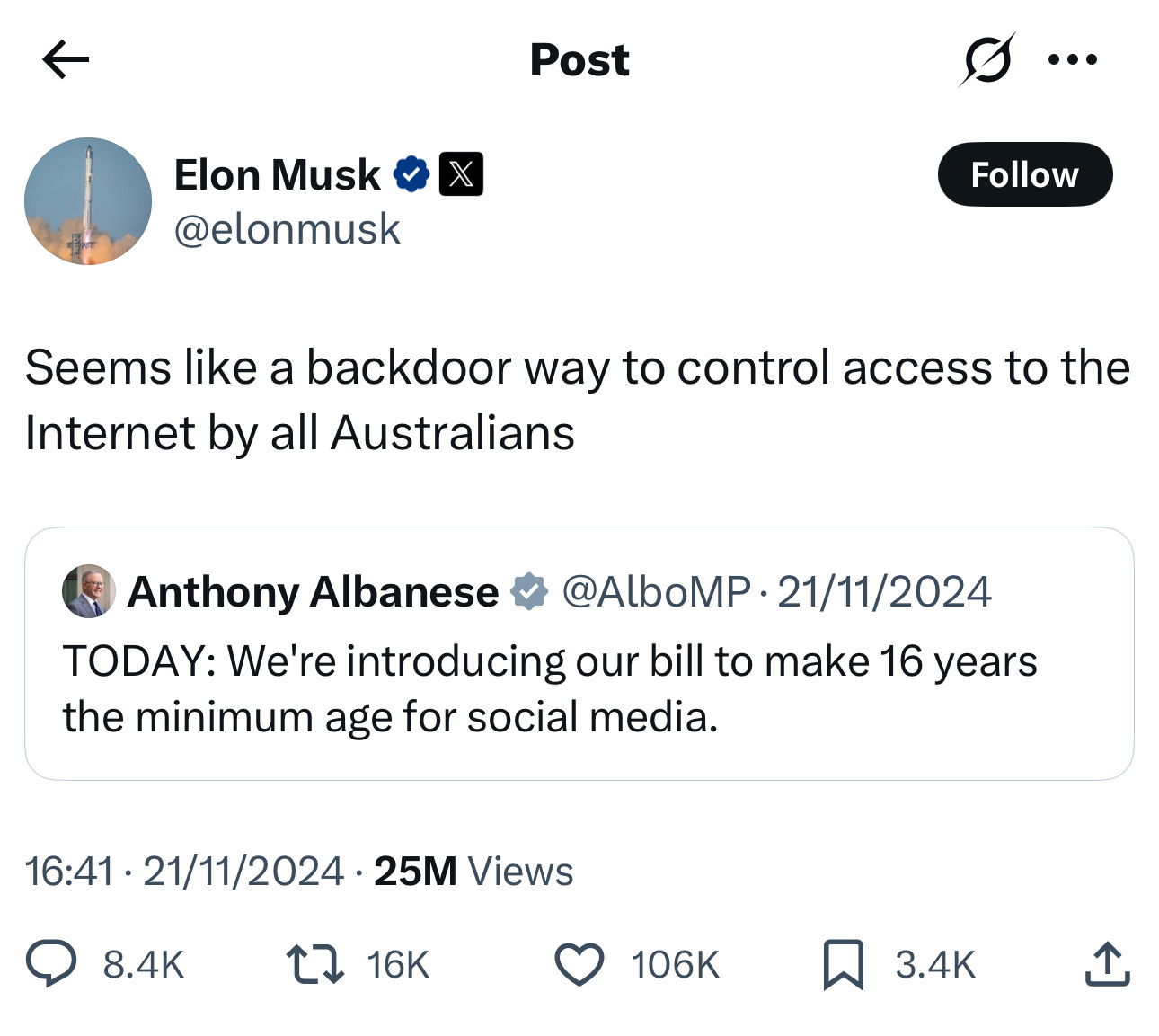

And if age verification wasn’t difficult enough, legal challenges and possible geopolitical tensions, only muddy waters further, with tech giants arguing the law restricts’s Australia’s freedom of speech and commercially discriminates against them. Unlike in the United States, Australia does not have a constitutionally entrenched freedom of speech, instead laws can restrict any ‘political expression’ if they are adequate and propionate to the issue the government is regulating.2 For instance, lawyers for X may argue the ban unfairly restricts the ability of under 16s from expressing political opinions online, or given that the majority of Gen Z consumes its news via social media, prevent them from being informed about current events. A similar anti-censorship defence was employed in eSafety Commissioner v X Corp, where the eSafety Commission demanded X remove videos of the stabbing of Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel globally, which the Federal Court held held was “unreasonable” and infringed on international conventions.3 Or, TikTok, who could argue the exemption on YouTube, a video streaming service with similar capacities as described of a ‘age-restricted social media platforms’, creates an unfair commercial advantage for YouTube which hosts rival short-form content ‘YouTube Reels’, and may attempt to have Federal Courts interpret YouTube to fall within the ban. Regardless, while the Albanese government and eSafety Commissioner may control compliance and enforcement, ultimately the Courts will have the last laugh on how the legislation operates.

Second, and most importantly, this law fails to meaningfully address the problem it claims to be resolving. The goal of the social media ban as pledged by former Communications Minister Michelle Rowland is “to keep children safe online”, however in legal effect, the law only prevents young people under 16 from signing up and does not curb the root problem affecting people young and old - screen time. Put simply, the internet is not going anywhere and while doomscrolling certainly helps no-one, social media consumption is symptomatic of wider issues around screen-time and algorithms which prioritise distressing and non-educational content to retain people’s attentions. Since 2024, on average users aged 16 to 64 worldwide spend 6 hours and 38 minutes per day on screens across various devices or 46 hours and 26 minutes per week amongst worldwide internet users. These numbers online were exasperated by the COVID-19 Pandemic which has seen a decline in people leaving their houses, with 48% of Americans not leaving their house everyday for variety of reasons. As a result, people people are failing to get outside and experience the world around them - this condition is often referred to as ‘cabin fever’ contributes to social isolation - a leading cause for mental health challenges amongst young people. The social media ban doesn’t impact YouTube, in particular its YouTube Reels service, which theoretically, young people under 16 will simply flock to get their dopamine fix once TikTok is inaccessible. This only leads to the question - does the social media as a result of its construction only delay inevitable doomscrolling to an arbitrary age of 16, rather than 13?

The social media ban’s supposed purpose of protecting young people inevitably operates closer to a marketing ploy towards the electorate than an actual legislative attempt at regulating the root problem in modern media consumption - algorithms. Mounting scientific evidence dating as far back as 2011 is revealing that social media algorithms are a primary contributor to raising mental health challenges amongst Gen Z and issues affecting society-at-large, including amplification of people’s biases, political polarisation and echo chambers restricting exposure to new ideas and concepts. A frequent example being online body standards, which data from the American Psychological Association demonstrate a strong connection to increased body dysmorphia and eating disorders amongst young people. A 2025 review found of male respondents exposed to ‘appearance-focused social media’ experienced a 25% increased risk of eating disorders. Or that the addictive nature of social media algorithms leads to an increased risk of anxiety and depression. The social media ban doesn’t address these issues and risks young people becoming more digitally illiterate and thus at greater risk of these issues once surpassing 16 years. These concerns were raised by Snapchat, in its submissions before Parliament on the Bill:

Many experts have highlighted the significant unintended consequences of this legislation, notably that it could deny young people access to valuable mental health and wellbeing resources, while potentially driving them toward less regulated and more dangerous online spaces than the mainstream, highly regulated platforms covered by the bill.

Snap Inc

However, despite these issues, social media does have benefits for young people, including organising communities online for people to engage in recreational activities such as video games, access unique communities such as TikTok’s #booktok and importantly engage in an increasingly digitised world. It also holds an economic advantage, enabling young people to advertise services and embrace entrepreneurial spirit from an early age. Paradoxically, social media also offers authenticity, especially amongst influencers and content creators where up to 63 % of teenagers already receive their news due to pre-existing scepticism of legacy media outlets.

Without these opportunities, Australia's young people will be prevented from engaging in an increasingly digitised society and upon becoming 16, will be placed at greater risk of the harms the Government says it’s protecting them from. In the meantime, while Australia’s social media ban may ‘protect’ young people in the short-term, it will only see them satisfy their dopamine fix from one platform to another.

Online Safety Amendment (Social Media Minimum Age) Act 2024 (Cth).

The High Court in a series of legal cases in the 1980s and 90s found the Australian Constitution holds an implied freedom of political communication, however this is not absolute.

Although, X’s steps to restrict the viewing of the video in Australia was deemed reasonable.